In US politics, conspiracies are rife – and many more emerged in the wake of the attempted assassination of Donald Trump. Tackling them requires us to see conspiracism differently, says researcher Sophia Knight.

Within minutes of Saturday's attempted assassination on former US President Donald Trump, conspiracy theories started to swirl online. Without any evidence, people spread claims that the incident was everything from a hoax to a plot. Swept up in a divisive presidential campaign, online voices spun up explanations to fill in the details of the day's shocking events.

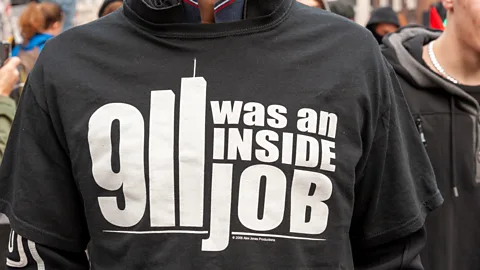

Conspiracy theories are not new in American politics. Adherents of QAnon – a wide-ranging political conspiracy movement – were among those who caused chaos at the Capitol on 6 January 2021, while there are many still invested in conspiracy theories regarding the assassination of former President John F Kennedy more than 60 years ago. From such experiences, we know the division, discord and disintegration of trust they breed can be extremely damaging to a democracy's health.

So, what do we do about this rising tide of conspiracism? Most importantly, the answer is not to just try and prove people wrong. Any attempt to debunk a conspiracy has a good chance of backfiring, playing into established narratives of "the elite" or "deep state" censoring the truth.

Comment & Analysis

Sophia Knight is a senior technology policy researcher at the UK think tank Demos.

In a recent report published by the UK think tank Demos and Everything is Connected – a research project at the University of Manchester – my co-authors and I argue that the first step is to change how we understand conspiracism. Conspiracy theories are not just bizarre curiosities festering on the fringes of society that are perpetuated by a handful of tinfoil-hat crazies. Nor do they emerge from thin air.

Rather, they are the result of a vicious cycle in which conspiratorial narratives emerge, are amplified and become fuel for ugly political fights. We call this dynamic the "conspiracy loop". Tackling conspiracism requires breaking the loop.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany proposed interventions for changing people's belief in conspiracy theories have been found to be ineffective. Conspiracies are often talked about as "spiralling out of control". But spirals are chaotic, runaway systems that quickly become unmanageable. The idea of a conspiracy loop offers a self-contained system on which we might have some hope of intervention.

In our report, we describe conspiracy loops as building and feeding back into themselves and they usually start with a "kernel of truth" from which most conspiracy theories evolve. In some cases this kernel is a literal "truth" – genuine conspiracies or secret plans by individuals or groups to do something harmful. In other cases, the "truth" refers to an environment of confusion, distrust, deficit and suspicion in which conspiracy theories flourish. The chaos and questions following the Trump assassination attempt offers an example of how these conditions can lead to speculation and disinformation quickly spreading.

More like this:

In other cases, those sharing conspiracy theories will be fully aware that the statements are not factually accurate, but they articulate a deeper feeling of truth that reflects their own lived experience.

When individuals and communities are unable to find meaning or explanations for the events in their own lives and the world around them, a space is opened up for alternative explanations. By dismissing "conspiracy theorists" as simply crazy, these individuals are pushed further to the margins, intensifying existing feelings of distrust and isolation.

The conspiracy loop results from a collision of technological, social and political dynamics, slowly building from an environment of distrust and suspicion into full-blown culture wars. By better understanding this process we can get a better idea of how to intervene.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesConspiracy loops build and feedback in three steps.

1. Generation

The loop starts with the generation of conspiratorial narratives at the grassroots level, in both online and offline spaces.

Often when groups feel marginalised, ignored or pushed to the fringes of society, conspiracy theories can function as an explanation for the struggles within their own lives. They offer a ready-made narrative for articulating potentially legitimate resentment or a justification of pre-existing beliefs.

In a political context, this generation stage starts when people feel overlooked and underserved – when politicians seem to ignore constituent voices and when new policies feel damaging or disrespectful of community needs and values.

2. Amplification

A small handful of fledgling conspiracy theories are picked up by conspiracy influencers and amplified to larger audiences, through a mix of mainstream and alternative social media platforms.

Prominent examples of conspiracy influencers include Alex Jones and David Icke, who have learned to use the structures of social media to build conspiracy empires, selling various documentaries, merchandise and even nutritional supplements.

3. Divergence

The final stage of the loop takes place once a conspiracy theory has fully emerged into the mainstream and is picked up by political figures and mainstream media outlets.

In recent years, there have been several high-profile incidents involving political figures spreading conspiratorial narratives. While some may be unknowingly playing into established tropes, others have opportunistically harnessed conspiracy theories to access pre-existing communities of support, boosting the power of their argument.

In the case of the attempted assassination of Trump, there has already been significant media and political commentary, some of which has repeated conspiratorial rhetoric. Most notably, Congressman Mike Collins of Georgia directly blamed President Joe Biden. He posted on social media that "Joe Biden sent the orders", referencing a comment the President had made earlier in the week about putting "Trump in a bullseye" of their election battle, something Biden has later admitted was a mistake.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBreaking the loop

In the wake of the attack, both Trump and Biden have called for unity and a de-escalation of political rhetoric. To protect our democratic societies, we may also need to break the conspiracy loop. If conspiracy theories continue to be dismissed as paranoid delusions that spiral out of control, distrust will continue to fester and conspiracism will continue to thrive. Instead it may be time for a deep examination of our democratic foundations. How else will it be possible to identify and address the genuine concerns, confusions and resentments that conspiracy theories often seek to explain?

*Sophia Knight is a senior technology policy researcher at the UK think tank Demos.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

.jfif)

Post a Comment