Elon Musk’s Starship rocket has completed a world first after part of it was captured on its return to the launch pad.

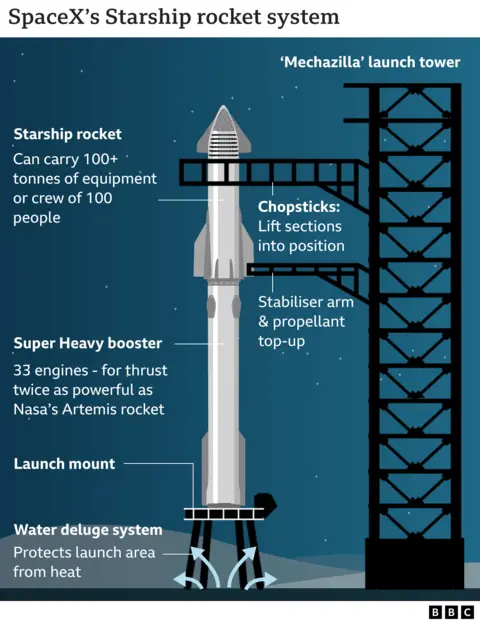

The SpaceX vehicle's lower half manoeuvred back beside its launch tower where it was caught in a giant pair of mechanical arms, as part of its fifth test flight.

It brings SpaceX’s ambition of developing a fully reusable and rapidly deployable rocket a big step closer.

"A day for the history books," engineers at SpaceX declared as the booster landed safely.

The chances of the bottom part of the rocket, known as the Super Heavy booster, being caught so cleanly on the first attempt seemed slim.

Prior to the launch, the SpaceX team said it would not be surprised if the booster was instead directed to land in the Gulf of Mexico.

SpaceX can now point to some extraordinary achievements in the past two test flights. This comes only eighteen months after its inaugural flight, which saw the vehicle blown apart not long after launch.

SpaceX argues that these failures are also part of its development plan - to launch early in the expectation of failure so that it can collect as much data as possible and develop its systems quicker than its rivals.

The initial stages of the ascent of the fifth test were the same as the previous outing, with the Ship and booster separating two and three-quarter minutes after leaving the ground.

At this point the booster began to head back towards the launch site at Boca Chica in Texas.

With just two minutes to go till landing it was still not clear if the attempt would be made, as final checks were carried out by the team operating the tower.

Reuters

ReutersWhen the flight director gave the go-ahead, cheers went up from SpaceX employees at mission control.

The company had said that thousands of criteria had to be met for the attempt to be made.

As the Super Heavy booster re-entered the atmosphere it slowed down from speeds in excess of a few thousands miles per hour.

When it approached the landing tower, which stands 146m-high (480ft), its raptor engines worked to control its landing. It seemed to almost float, orange flames engulfed the booster and it deftly slotted into the giant mechanical arms.

Reuters

ReutersThe Ship part of the rocket, which is where equipment and crew will eventually be held for future missions, fired up its own engines after separating from the booster.

It was successfully landed in the Indian Ocean around forty minutes later.

"Ship landed precisely on target! Second of the two objectives achieved", SpaceX CEO Elon Musk wrote on X.

Not only was the Ship landed accurately but SpaceX also managed to preserve some of the vehicle's hardware, which it had not expected.

Catching the booster rather than getting it to land on the launch pad reduces the need for complex hardware on the ground and will enable rapid redeployment of the vehicle in the future.

Elon Musk and SpaceX have grand designs that the rocket system will one day take humans to the Moon, and then on to Mars, making our species "multi-planetary".

The US space agency, Nasa, will also be delighted the flight has gone to plan. It has paid the company $2.8bn (£2.14bn) to develop Starship into a lander capable of returning astronauts to the Moon's surface by 2026.

In space terms that is not that far away so Elon Musk's team were eager to get the rocket re-launched as soon as possible.

But the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) , the US government body that approves all flights, had previously said there would be no launch before November as it reviewed the company's permits.

Since last month the agency and Elon Musk have been in a public spat after the FAA said it was seeking to fine his company, SpaceX, $633,000 for allegedly failing to follow its license conditions and not getting permits for previous flights.

Before issuing a license, the FAA reviews the impact of the flight, in particular the effect on the environment.

In response to the fine, Musk threatened to sue the agency and SpaceX put out a public blog post hitting back against "false reporting" that part of the rocket was polluting the environment.

Currently the FAA only considers the impact on the immediate environment from rocket launches rather than the wider impacts of the emissions.

Dr Eloise Marais, professor of atmospheric chemistry and air quality at University College London, said the carbon emissions from rockets pale in comparison to other forms of transport but there are other planet-warming pollutants which are not being considered.

"The black carbon is one of the biggest concerns. The Starship rocket is using liquid methane. It's a relatively new propellant, and we don't have very good data of the amount of emissions that are coming from liquid methane," she said.

Dr Marais said what makes black carbon from rockets so concerning is that they release it hundreds of miles higher into the atmosphere than planes, where it can last much longer.

Post a Comment