Earthships are designed to withstand the extreme temperatures of a desert, such as that around Taos, where extreme weather runs from sub-zero in winter to sweltering in summer.

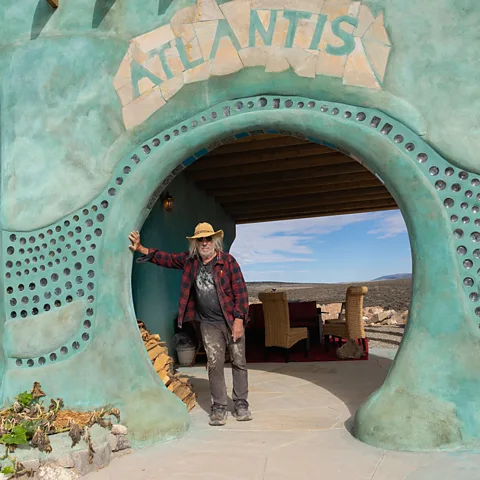

Venture into New Mexico's beautifully stark high desert and you may well stumble across some fantastical and unconventional homes – some palatial and sculpturally rounded; others with an ancient temple-like form – that look like they're from a Star Wars movie.

Set in and around the town of Taos where they were invented almost 40 years ago, these are Earthships: net-zero, sustainably designed homes built mostly from both natural and waste materials, such as old tyres, empty wine bottles and wood and mud.

Since Earthship construction requires less in the way of toxic or carbon-emitting construction materials like concrete and plastics, and doesn't require precious woodland and other natural resources, these exquisite homes are increasingly sought after worldwide. Earthships sell for anything from around $500,000 to $900,000 (£376,000 to £677,000) and are also available for overnight stays in and near Taos for around $240 (£180) per night.

The Earthship movement began in Taos in the 1970s after Kentucky native Michael Reynolds, founder of eco-construction company Earthship Biotecture, moved here in 1969 with an architecture degree. His goal: to "ride dirt bikes, for fun," he says.

The now-71-year-old soon had an a-ha moment.

Earthship Biotecture

Earthship Biotecture"I saw [CBS News anchor] Walter Cronkite on the news talking about clear-cutting forests for timber and creating not only erosion, but an oxygen problem because the trees put out oxygen," Reynolds tells the BBC. "He was talking about what we call climate change and global warming now. I was seeing all these beer cans tossed away and I'm saying, 'why don't we build out of beer cans and not trees?'"

GREEN GETAWAYS

Green Getaways is a BBC Travel series that helps travellers experience a greener, cleaner approach to getting out and seeing the world.

Reynolds built his beer-can house in 1971, gaining small notice in the news for its quirkiness. Yet, it went on to be exhibited in various parts of the world, including the Louvre Museum in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Reynolds notes, with some incredulity, "MoMA just bought a beer can brick for $4,500 (£3,386)." Indeed, after using one of the building blocks made of beer cans in an exhibit, the museum decided to add one to its permanent collection.

"It was a kind of a pie-in-the-sky ridiculous idea, but I went ahead and started going in that direction," Reynolds says. "I started using bottles and I started using tyres, and I kept going. I've been in this direction for easily 55 years, and then around 36 years ago I first labelled a home as an Earthship."

Earthship Biotecture

Earthship BiotectureBut it's taken a long time to get to the point of wider acceptance. "You know, they looked too weird and they still look strange, but now people are getting it, and they're also open to it because [many people] are two paycheques away from being homeless and getting crippled by electric and utility bills," Reynolds says of the financially empowering aspect of living off-grid. "And now people want to reverse climate change."

Taos is a place that has long attracted artists and individualists. Its ancient pueblo (village) and newer town have striking architecture, mostly traditional viga-beamed adobe homes, whose roofs are made of wood and beaten earth. Taos was the perfect incubator for Earthships, which have a thick wall of tyres, each packed with earth.

An earth berm (a purposefully built bank of soil) surrounds the Earthship on three sides, providing insulating mass that controls temperature. Cooling is via traditional transom windows set up high on supporting beams to cross ventilate, and the building's pipe vents. Each has a greenhouse (as Reynolds believes people should have to ability to grow their own food), either on the north or south side depending on location. Most Earthships are purely solar powered; some also have wind turbines to supplement or a wood-burning stove as back up.

Taos has cold snowy winters and often dry, hot summers, but in an Earthship, the internal temperature remains close to 72F (21C) year-round, regardless of outside weather conditions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesReynolds moved into his first Earthship 35 years ago, he says, and raised his family there – he still lives there: "It's so comfy we don't want to leave it," he shrugs.

What does it feel like to stay inside an Earthship? "It feels like you're inside the womb," says Earthship construction manager Deborah Binder. "You feel constantly hugged and snuggled. The temperature is always comfortable. Sometimes, when it's really cold outside I'll walk out without a coat not realising, because it's so warm inside."

Binder came on board 11 years ago to manage a non-profit project in Malawi, Africa, without any background in construction, she says. Not only did she stay with the company, she moved to Taos and currently rents an Earthship while she builds her own. Binder also teaches at the Earthship Academy, which attracts attendees of all types to learn Earthship design principles, construction methods and philosophy.

"Most people want to learn for themselves," Binder says. "Some learn to build for community projects."

Despite their environmental appeal, Earthships are still not accepted as an option to ease the housing and climate change crisis. "They're still on the fringe in a way," says Binder. "It's really important for people to stay in one. The feeling you have living in them is unique, but on a practical level you don't pay any utility bills. That's quite amazing."

Earthship Biotecture

Earthship Biotecture"Once people experience them, they usually want one," Reynolds adds, something that is borne out by the many glowing testimonials in the guestbooks placed in each Earthship rental.

Reynolds believes it could not be more timely – urgent even – to make Earthships the norm. His goal is to build rentable community housing as an answer to homelessness and planet-devastating energy consumption. "I'm not that interested in commissions; having a client just slows me down," he says. "I need to turn them out fast and lease them to people for a fair rent."

CARBON COUNT

The travel emissions it took to report this story were 0 metric tons of CO2e. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

Reynolds is full steam ahead with his latest streamlined Refuge Earthship model, which he thinks could help with homelessness and poverty due to the simple economics of not paying huge utility bills each month. "Refuge is the most economical model to build; the one we are going to replicate all over the globe," he says passionately.

"There is an art side to them — I've played with the bottles as stained glass, and there's the sculptural aspect. They are beautiful," says Reynolds, who put himself through college by working as an artist. "What's really beautiful is they take care of people while taking care of the planet. There is not as much meaning in art as there is in a home."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

Post a Comment