Rachel Nuwer gets a firsthand look at a unique fermentation method being piloted in Japan to transform edible leftovers and scraps into sustainable feed for pigs while saving money, reducing waste and curtailing emissions.

Even as a boy, Koichi Takahashi knew he wanted to save the planet. He dreamed of building a future society that sustainably coexisted with nature through a loop of recycling and regeneration. Takahashi knew he couldn't remake the entire world himself, but as he got older, he realised that he could focus his energy on reforming one small corner of it.

Pig farms were the unlikely target that Takahashi settled on for his life's work. Specifically, he founded a company, the Japan Food Ecology Center, that creates a win-win solution by turning leftover human food into high-quality pig feed. "I wanted to build a model project for the circular economy," he says. "Instead of relying on imports for feed, we can make effective use of local food waste."

Japan's small size and mountainous terrain present challenges for food self-sufficiency. The country imports almost two-thirds of its food and three-quarters of its livestock feed. Yet each year, Japan throws out 28.4 million tonnes of food – much of it edible.

This comes with steep environmental and economic costs. Compared to many countries, consumers in Japan pay higher prices for food because so much of it is imported. And they also pay taxes to cover the majority of the 800bn yen (£4.2bn/$5.4bn) the country spends each year on waste incineration. Food makes up about 40% of the rubbish that Japan incinerates, and incineration produces significant air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

As the world's fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, Japan has set goals of cutting emissions by 46% by 2030 and becoming fully carbon neutral by 2050. Tackling food waste will have to be a part of those efforts, Takahashi says.

Ancient science, new solution

Takahashi's vision for creating a sustainable food loop was sparked in 1998 when the Japanese government launched a project promoting ways to convert otherwise wasted resources into livestock feed. The price for imported grain was rising at the time, and there was "a sense of crisis in Japan", Takahashi recalls. People felt the livestock industry would collapse if a solution was not found.

:Rachel Nuwer

:Rachel NuwerTakahashi, who was then a practicing veterinarian, sensed an opportunity to put his farm animal expertise to use – and to simultaneously fulfill his desire to help the planet. As he learned more, though, he found there were no quick fixes, as simply sending raw food waste to farms was difficult. Major issues complicated the matter, including the highly varied content of food waste; the fact that food's high water content promotes spoilage; and that drying the food out to get around the water problem would require nearly as much energy as incinerating it.

To come up with a solution, Takahashi turned to a natural art that Japan has been perfecting for millennia: fermentation. "I realised that we already had the technology to create a product that could last long," he says.

Japan's long history of fermentation

Japan has a special relationship with fermentation. There is some archaeological evidence to suggest people began fermenting berries there during the early Jomon period around 5,000 years ago. Today fermented foods, beverages and seasonings enjoy a central place in Japanese food culture. Japan even has its own accredited fermentation sommeliers.

And the country is also a leader in fermentation science – a field of study that spans innovations ranging from biofuel development to antibiotic discovery.

Partly, Japan's ability to excel at fermentation science has stemmed from its researchers' distinct approach to microbes, says Victoria Lee, a historian at Ohio University. Japanese microbiologists "went in a whole different direction" compared to their colleagues in North American and Europe, where the focus was on pathogens and germs, Lee says. Rather than view microbes as enemies, in Japan, a tradition emerged of "seeing them as powerful partners".

Fermentation has been a subject of scientific study in Japan since the 19th Century, when the government began investing heavily in building new industries based on ancient practices like sake brewing and soy sauce-making. By the 20th Century, the country's focus on fermentation led to a distinctly Japanese approach in which microbes were seen "as living workers", says Victoria Lee, a historian at Ohio University and author of The Arts of the Microbial World: Fermentation Science in Twentieth-Century Japan. "To scientists, more than a food process, fermentation became a way to transform society and solve various environmental and resource problems."

Like the fermentation researchers who came before him, Takahashi was looking for a way, as Lee puts it, "to take what might otherwise simply be waste and transform it into something useful, in the process creating new industries."

Working with researchers from government, universities and national institutes, Takahashi used his veterinary knowledge to craft a lactic acid-fermented, liquified feed product for pigs. The team had to engage in lengthy troubleshooting. "When we fed the early test feed to the pigs, they grew slower and their meat was too fatty," Takahashi recalls. Over the course of "a series of failures", they eventually got the nutritional content right. They also found a way to extend the shelf life of the "ecofeed", as they called their product, by lowering the pH to 4.0, a level at which most pathogenic bacteria cannot survive.

The resulting product – pale and watery – tastes like sour yogurt, Takahashi says, and can sit on a shelf, unrefrigerated, for up to 10 days. The product is also a boon for the climate: compared to the equivalent amount of feed imported from abroad, Takahashi says, the ecofeed manufacturing process generates 70% less greenhouse gas emissions.

As the science fell into place, Takahashi began lobbying the government and various other stakeholders to allow him to move forward with bringing the centre's recycling loop system to market. It took years, but "we have now built a relationship of trust" with various government bodies that oversee waste and environmental issues, he says. Government officials, in fact, "frequently come to us for advice".

Profitable and sustainable

Most waste treatment plants smell like, well, waste. Visitors to the Japan Food Ecology Center are often surprised by the lack of pungency. If anything, the air is reminiscent of a smoothie shop.

The centre is located in Sagamihara, a city in Kanagawa prefecture that's about two hours by train from Tokyo. Sagamihara itself is unremarkable, but every year some 1,500 visitors from around Japan – from elementary students to retirees – visit the centre to learn firsthand about food recycling.

The facility processes about 40 tonnes of food waste per day, which arrives by truck from several hundred supermarkets, department stores and mass manufacturers. Some of these businesses are motivated by a desire to green their operations, but all are incentivised by the lower fees that the centre charges to accept their waste, compared to incinerators. The foods they send vary by day, but whey, a byproduct of butter and cheese, is an ever-present staple, as are scraps from mass production of things like gyoza and sushi. Any manufacturing process results in an unavoidable 3% to 5% product loss, Takahashi says, so a factory that makes 50 tonnes of food per day will generate at least 1.5 tonnes of waste.

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerLarge amounts of food waste are also produced by manufacturers that are contracted to supply Japan's 55,657 convenience stores – many of which are open 24 hours, 365 days a year – with a constant stream of products. Perishable food for convenience stores "must be delivered as soon as it's ordered, so factories that make boxed lunches and rice balls are required to produce extra, even if they lose some", Takahashi says. "Because of the importance placed on preventing lost sales opportunities, large amounts of food waste have become routine."

Fermenting fish bones

Makoto Kanauchi, a fermentation scientist at Miyagi University in Sendai, uses science to refine and expand upon age-old fermentation techniques. “Cultivating good microbes to drive out bad ones is the origin of fermented food,” he says. Kanauchi is constantly experimenting with new fermented food types, including a soy sauce made from puffer fish bones. He also has also made a silky, spreadable soymilk-based cheese and a fermented fish sauce-like seasoning made with plankton.

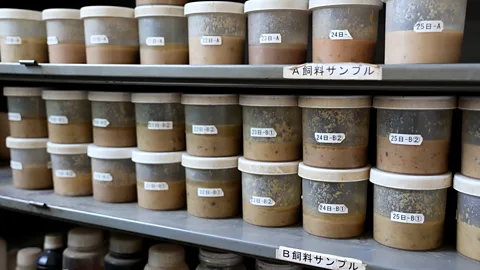

On a recent morning, an assortment of 140 and 500-litre containers filled with gyoza skins, rice, cabbage, pineapple rinds, bananas, noodles and sandwich buns awaited processing. Batches of ecofeed are calibrated based on caloric and nutritional content, so various materials are mixed with intent rather than at random. To prevent contamination, all of the food is passed through a metal detector and inspected by hand by workers at a conveyor belt. Chopping and crushing comes next, resulting in a liquid product (on average, 80% of food is water), followed by sterilisation to reduce pathogenic bacteria. Finally, the liquid is fed into one of several huge tanks where fermentation occurs, thanks to the bacteria in the lactic acid.

The resulting ecofeed costs farmers about half the price of conventional feed, and farms can also tailor their personal formula according to their needs – requesting more lysine or other amino acids, for example, to increase fat or muscle mass in their pigs.

According to Dan Kawakami, a farmer at Azumino Eco Farm in Nagano that has been supplied by the centre since 2006, the quality of pork from animals raised on ecofeed is better. Using a sustainable feed source "also differentiates our product from competitors", he says, "and it's beneficial in terms of cost".

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerEco-pork from farms like Azumino is carried by an ever-growing list of dozens of restaurants, supermarkets and department stores around the country, and generates more than 350m yen (£1.8m/$2.3m) in annual sales, says Takahashi. "It's becoming popular as a meat that's both delicious and sustainable," he says.

Last year, Takahashi also got into biogas – a form of renewable energy produced from methane fermentation. The biogas operation expands the types of food that the plant can accept, since the pigs cannot have anything with too high a fat, salt or oil content. In towering 1,500-tonne vats – the bubbling contents of which resemble the Bog of Eternal Stench from the movie Labyrinth – scraps are mixed with water and heated to produce fermentation. An electric conversion generator turns the resulting methane into electricity, which Takahashi sells back to the grid.

More like this:

The plant is currently generating 12,672kWh of electrical output per day, about the same amount used by 1,000 households. The solid byproduct of the process – a powdery black substance that smells like a savoury seasoning – is dried using the generator's surplus heat and is sold as a nutrient-rich agricultural fertiliser. As Takahashi notes, "nothing is wasted".

Importantly, the centre is making a profit off the 35,000 tons of food waste it processes each year. "We're subverting the conventional notion that environmental efforts don't pay, or that recycling is just too expensive," Takahashi says. Because his goal is "to change society", he adds, he did not take out any patents on the technology, allowing others to replicate his method. His centre has served as a blueprint for other facilities in Japan that use his fermentation method. Together, they produce more than one million tons of ecofeed a year and prove that "an ecological, sustainable effort can be profitable", Takahashi says.

Takahashi also regularly hosts students, scholars and industry executives from around the world who come to learn about fermentation and food waste. Coming full circle, he likes to end the tours he takes them on with the pork itself, so people can judge its quality for themselves. It's served tonkatsu-style – deep fried, and with sides of rice and salad that are produced by the same farm. As for the pork, it's shockingly tender, with just the right ratio of fat to juicy muscle. The same meal is served three times a week to the centre's staff, Takahashi adds, "to motivate them by tasting how good the pigs fed by their own products are".

Rachel Nuwer is a freelance science journalist and author based in New York City. Her reporting in Japan was supported by a grant from the Abe Fellowship Program, administered by the Social Science Research Council and the Japan Foundation New York.

* An earlier version of this article stated that the biogas plant generates 528kW of electricty a day. This has been corrected to 12,672kWh.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and X.

Post a Comment