The much-anticipated follow-up to The Handmaid’s Tale is finally here. It is chilling and intense, but does it live up to its predecessor? Laura Freeman gives her verdict.

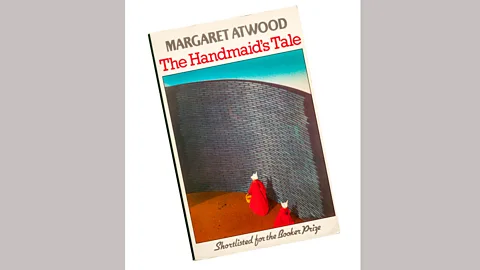

Strange the things that stay with you, what you remember and what you forget. If someone had said “The Handmaid’s Tale” at any time in the 18 years since I first read Margaret Atwood’s dystopia, one scene would have come to mind: the Ceremony, the ritualised rape of the Handmaid Offred by the Commander, while Offred rests her head in the lap of his wife. Nothing else in the book – not the hangings, the scapegoatings, the slut-shamings, the unbabies – had the power of that menacing ménage a trois.

More like this:

“Which of us is it worse for, her or me?” wonders Offred. Both women, fertile chattel and barren wife, are debased; both suffer a peculiar humiliation. The Wives, Handmaids and domestic Marthas of Gilead are helpmeets, vessels and servants. They have no right to work, earn, talk back, walk alone. They have no right to read and no right to pleasure. It’s unclear which of these Atwood considers the greater wound.

Alamy

Alamy“‘It can’t happen here’ could not be depended on,” writes Atwood in her introduction to the 2017 edition of The Handmaid’s Tale. “Anything could happen anywhere, given the circumstances.” The Testaments, published next week, sets out, in part, to answer the question that has appalled readers since The Handmaid’s Tale was published in 1985: “How did it happen?”

This book arrives shrouded in secrecy: modest bonnet, long robes, lowered eyes. Never have I had such difficulties getting hold of a book to review – it turns out, this might have been easier if I’d ordered it on Amazon. Even the Booker Prize judges were given watermarked manuscripts to be locked in drawers. Embargo. Omertà. Loose lips sink ships.

At the same time, never have I known such hype and hoopla. Worldwide launch. Midnight readings. Appearances by Atwood talked up like God on the Holy Mount. The windows of Waterstones book shops acidly green.

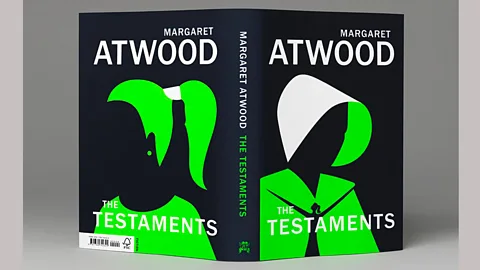

Penguin/ Random House

Penguin/ Random HouseWhen it arrives, a courier appears on the stairs. Motorcycle helmet. Black leathers. Visor down. As he turns around I half expect to see the Eye of Gilead embroidered on his back. The book comes in a jiffy bag stamped: “All things come to she who waits.” On the front cover: a handmaid in her distinctive cloak and bonnet. On the back: a girl with a ponytail and a single earring. Servitude and freedom; modesty and anarchy. The green satin bookmark is a nice touch. A little flicker between the pages, like the tail of the serpent in the Garden of Eden. He started it, you know, not Eve.

Readers of The Handmaid’s Tale and followers of the MGM/Hulu TV adaptation have been speculating: is it a prequel or a sequel? And is it the equal of its Handmaid mother? The answer to the first question is: both. The prequel part deals with the illicitly-kept history of Aunt Lydia, one of Gilead’s instructresses of female morality, as she remembers how ‘It can’t happen here’ happened. “I’d believed all that claptrap about life, liberty, democracy, and the rights of the individual I’d soaked up at law school,” Aunt Lydia writes. “These were eternal verities and we would always defend them. I’d depended on that as if on a magic charm.”

The chapters in which Aunt Lydia writes of her arrest, the end of her career as a “so-called lady judge”, and her internment in a sports stadium are among the most chilling in the book. They recall in their indignity and intensity the story of French Jews waiting in the Vélodrome d’Hiver in Paris to be deported to the Nazi death camps. It doesn’t take much – filth, hunger, fear – to make her an unwilling willing servant of the regime.

Fact and fiction

The sequel chapters are narrated by two teenage girls: Agnes in Gilead, Nicole in Canada. I thought I’d been clever to work out who these girls are. Too obvious, too early. Now having read the coda – The Testaments ends, as does The Handmaid’s Tale, with a transcript from a future academic Symposium on Gileadean Studies – I’m wavering. Atwood demands scepticism. What is fact, what is fiction, who destroys the evidence, who lives to tell the tale? “Gilead news is saying it’s all fake,” says one of the characters. Sounds familiar.

In both books the Marthas are always baking. You sense Atwood kneading her dough, shaping her gingerbread women, leaving paths of breadcrumbs. There are clues and echoes and trails to be picked up by readers: May Day, Moon June, Commander Judd, the Underground Female Road. That’ll get the fan-girl forums going.

In two important respects, however, this is a weaker and less satisfying look. The first is voice, the second is place. The Handmaid’s Tale (singular) was one woman’s telling. We look from under Offred’s headdress, we stare at her bedroom ceiling. The Testaments (plural) divides our attention and sympathies between three interleaved stories. We are with Nicole, Agnes and Lydia, but we are Offred. As for space, The Handmaid’s Tale was a chamber piece. Gilead, as Offred knows it, is bedroom, house, daily walk. She has no book, no occupation, not even the knitting allowed to Serena Joy. The rapes aren’t the worst of Gilead. It’s boredom that kills. “The long parentheses of nothing.”

Alamy

AlamyThe Testaments is all over the place: bus, boat, van, woods, river, sea, school, dentist, diner, hotel, condo, charity shop, refugee centre. The later chapters turn into a road-tripping buddy-movie with prayerful Agnes and kick-ass Nicole as the mismatched odd couple. Three of the Nicole scenes are so obvious, so made for a film franchise – The Hunger Games in bonnets – that I almost laughed. There’s a Karate Kid montage as Nicole learns to fight, a tough-girl makeover complete with tattoo and green hair and a night spent by Nicole, chastely, in the arms of the muscular, yet sensitive, Garth.

Agnes and Nicole, unformed and formulaic, are less interesting than Offred. They are innocents where Offred knew experience. One of the things that makes The Handmaid’s Tale such a tricksy, defiant book, is that Offred remembers sex before it was sinful and supervised. She remembers the pleasure of seduction and shared joy. She aches to be touched, she swings her hips to tempt a young guard, she feels the thrill of “enticement” wearing a sequinned bodysuit, she risks her life to make love to a forbidden man. Agnes and Nicole are virgins and so the tension of sex, whether endured or longed for, is gone.

MGM/ Hulu

MGM/ HuluThe horrors and repressions of Gilead, so shocking on first encounter, so convincingly realised, are here repeated. If you’ve seen one ululating birth, one man torn apart by Handmaids, you’ve seen them all. Atwood’s prose is as powerful as ever, tense and spare. She invests certain phrases with ironic fury: adulteress, precious flower, Certificate of Whiteness, fanatics, defiled. Her word games are ingenious. She forces you to think about language and how it can be made to lie. The plot is propulsive and I finished in six hours flat. But if The Handmaid’s Tale was Atwood’s mistresspiece, The Testaments is a misstep. The Handmaid’s Tale ended on a note of interrogation: “Are there any questions?” Those questions were better left unanswered.

★★★☆☆

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood is published by Penguin/ Random House, £20

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Post a Comment