Leaders and representatives from nearly every country on Earth are meeting in Colombia to take stock of global progress in protecting the natural world.

The United Nations biodiversity summit, known as COP16, comes amid growing concerns over plummeting populations of plants and animals, and damage to the habitats that sustain life on earth, from forests to rivers and oceans.

At the last UN global summit on biodiversity, held in December 2022, nearly 200 countries signed up to an ambitious plan to reverse nature loss by the end of the decade.

The Cali summit is expected to be the biggest of its kind - and the first chance to hold leaders to account over their national plans for protecting nature.

What is biodiversity and why is it important?

Biodiversity is the variety of all life on Earth - animals, plants, fungi and micro-organisms like bacteria.

Together they provide us with everything necessary for survival - including fresh water, clean air, food and medicines.

However, humans cannot get these benefits from individual species - a rich variety of living things must work together in tandem.

Plants are very important for improving the physical environment: cleaning the air, limiting rising temperatures and providing protection against climate change.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMangrove swamps and coral reefs can act as a barrier to erosion from rising sea levels.

Trees found in cities such as the London plane or the tulip tree, are excellent at absorbing carbon dioxide and removing pollutants from the air.

How many species are at risk of extinction?

It is normal for species to evolve and become extinct over time - 98% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct.

However, the extinction of species is now happening between 100 and 1,000 times more quickly than scientists would expect.

As a result, many scientists warn humans could be causing the "sixth mass extinction" on Earth.

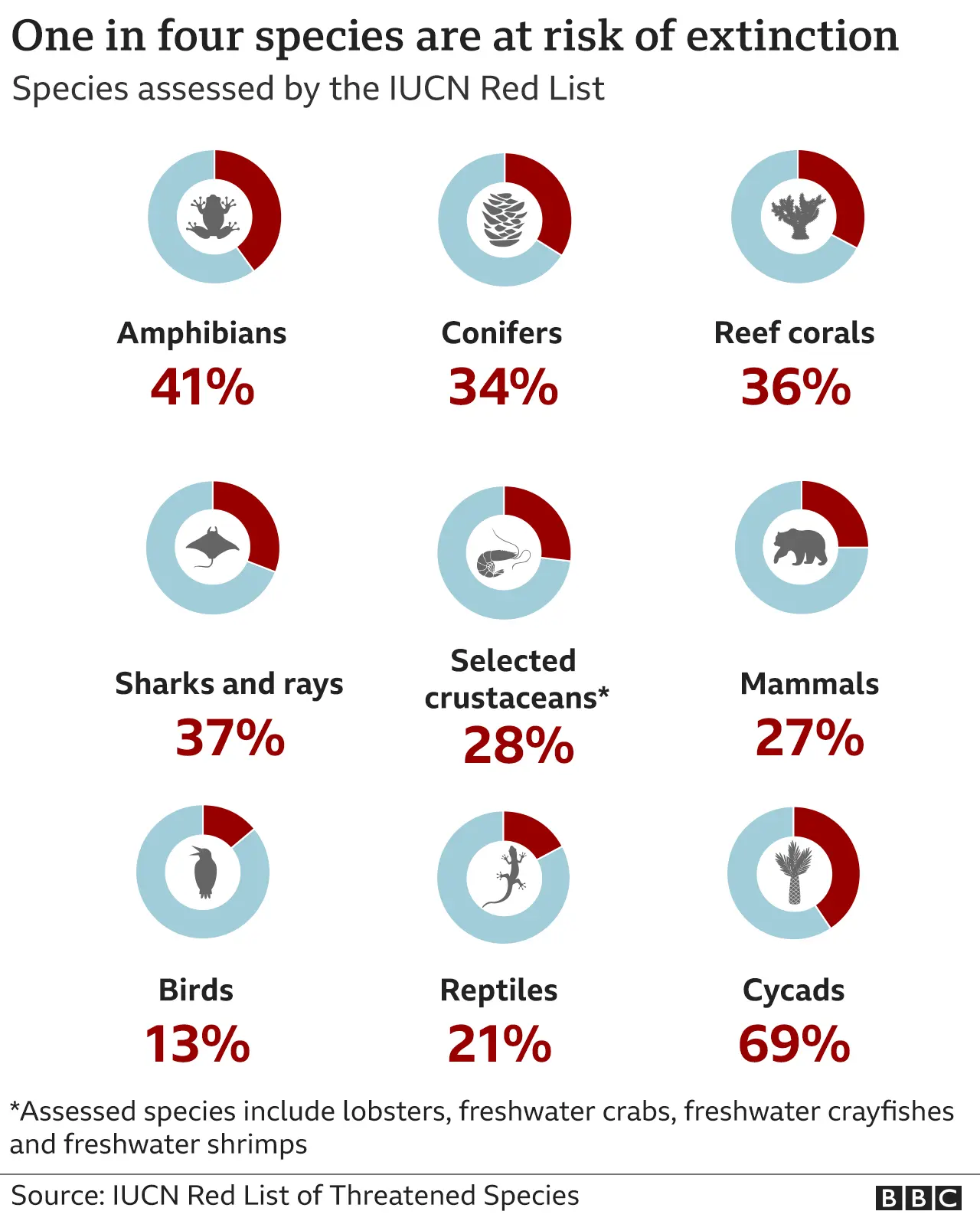

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has kept a "red list" of threatened species since 1964. More than 163,000 species have been assessed, and 45% are considered to be threatened with extinction.

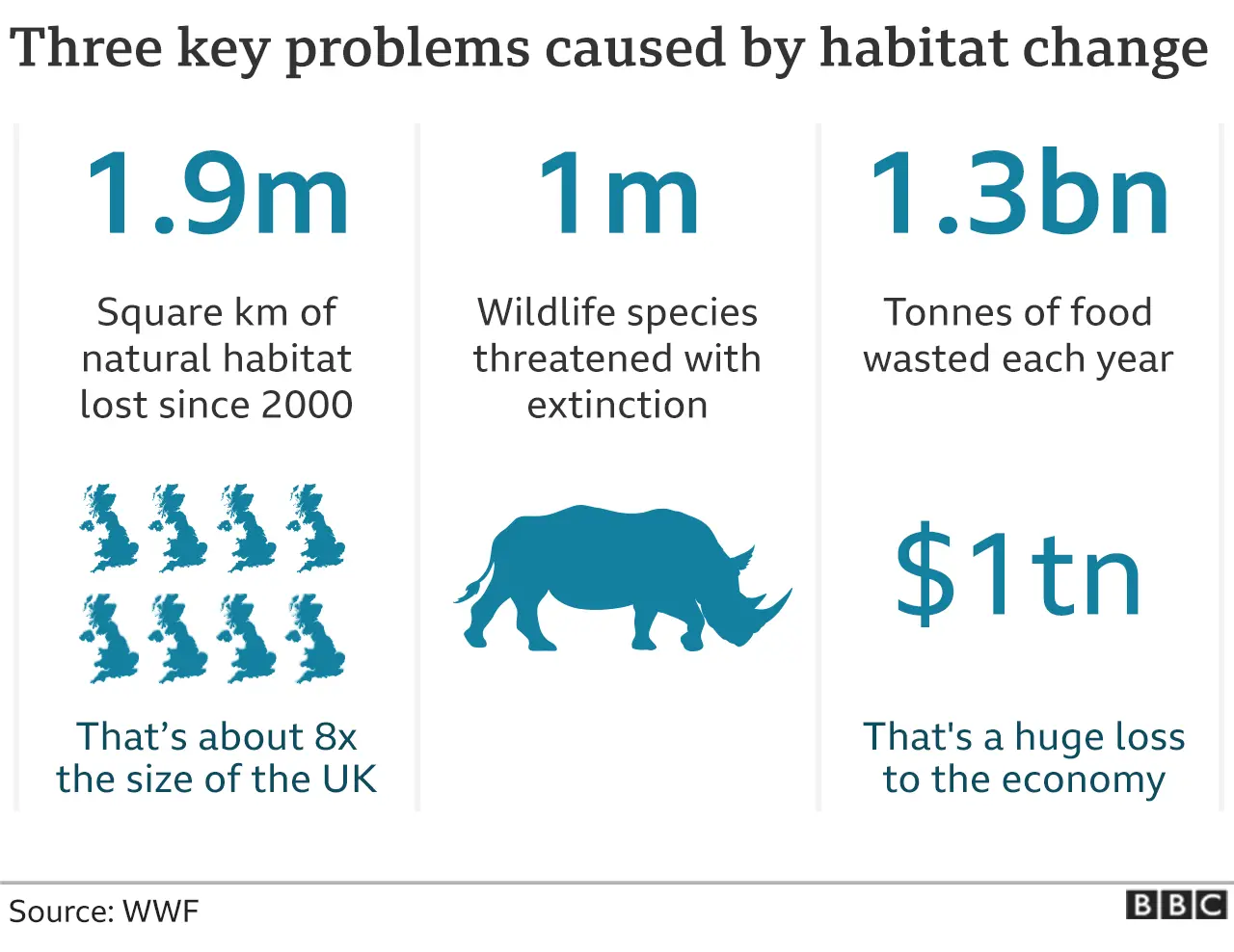

The UN's biodiversity body - known as IPBES - estimates that at least one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction - and humanity is largely to blame.

But the threat of extinction varies enormously. For example, it is estimated that 40% of amphibians (a group that includes frogs and toads) are at risk.

In addition, for some groups - such as insects and fungi - not enough species have been evaluated to be able to accurately assess the risk.

What are the biggest threats to biodiversity?

In one recent report, IPBES highlighted the damage done by harvesting, logging, hunting and overfishing.

Between 2001 and 2021 the world lost 437 million hectares of tree cover - 16% of which was primary forest. The destruction of mature forests, which have taken hundreds - if not thousands - of years to develop, can have a very serious impact on biodiversity.

Biodiversity loss is occurring worldwide, according to the WWF.

Recent losses have been highest in Latin America, where animal populations have declined by 95%, mainly due to habitat destruction and overexploitation.

The Natural History Museum in London says the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in Europe, and is in the bottom 10% globally.

The rate of climate change is also increasingly difficult for animals and plants to cope with, the UN warns.

It says that limiting global temperature rises to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels is important to prevent even greater losses of biodiversity.

What have countries agreed to do to tackle the issue?

At the UN's COP15 summit on biodiversity in December 2022, countries reached an "historic" agreement to protect 30% of Earth's land and seas by 2030.

The agreement - known officially as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework - aims to "halt and reverse" biodiversity's decline by 2030, and for humans to live "in harmony with nature" by 2050 to deliver "benefits essential for all people".

It has four main goals:

- increased conservation of ecosystems and species

- resources used as sustainably as possible

- more equal sharing of natural resources

- increased financial support for biodiversity protection

There are 23 more specific targets for 2030, including mechanisms to finance conservation projects in biodiversity hotspots. Governments and private organisations are pledging to give at least $200bn (£161bn) per year by 2030.

As part of this richer countries have promised to increase the amount of money they give to poorer countries for biodiversity projects to $30bn per year by 2030.

Although the 2022 framework was not legally binding, signatories committed to demonstrating progress towards meeting biodiversity targets.

What is COP 16?

From 21 October until 1 November, delegates are meeting in Cali, Colombia to take stock of national pledges to protect nature, amid concerns countries are back-sliding on their promises.

Recent analysis suggests most countries are set to miss the deadline to submit new national action plans for preserving nature.

Key issues include the scale of ambition in meeting specific targets, finance for biodiversity projects in poorer countries and making sure profits from genetic resources are shared fairly.

Colombian environment minister, Susana Muhamad, who is overseeing the meeting, has set the theme, 'Peace with Nature', a call to rethink our relationship with the natural world.

Several presidents are expected to attend, including Brazil's Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Mexico's incoming president, Claudia Sheinbaum.

.jfif)

Post a Comment