From the self-indulgent to the tiresomely macho, Hephzibah Anderson chooses her picks of previously hip books that have not aged well.

What exactly defines a cult book? Its qualities are subjective, often intangible and niche, though we all know one when we see it. Think Mervyn Peake’s quirkily gothic Gormenghast novels or The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter’s seminal reworked fairy tales. Think Doris Lessing’s radical showstopper, The Golden Notebook, or The Dice Man by Luke Rhinehart, a countercultural yarn still spoken of in rapt tones by its acolytes.

This article was originally published in September 2019.

More like this:

What’s certain is that the cult classic inspires passionate devotion among its fans, who frequently weave their own myths around the texts. But another, underexamined, feature of the cult book is this: in contrast to the examples above, it can sometimes age really badly. Every bit as badly as giant shoulder pads, velour tracksuits and platform hiking boots.

We’ve taken a blushing look back at some of the formerly hip tomes now shelved in that spectral section of the bookshop reserved for the irredeemably dated, the hopelessly irrelevant, the plain offensive. Their fate tells us a little something not only about why cult novels fade but also about how they’re made in the first place.

If there’s one lesson to be learned, it’s this: stay sceptical, dear reader. Don’t, for instance, rush to empty your home of anything that doesn’t ‘spark joy’ at the behest of a book that may yet turn out to be our own era’s Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Then again, if you do still have a copy of that particular avian-inspired title lurking in your bookcase, now might be a good time to pay a visit to the charity shop.)

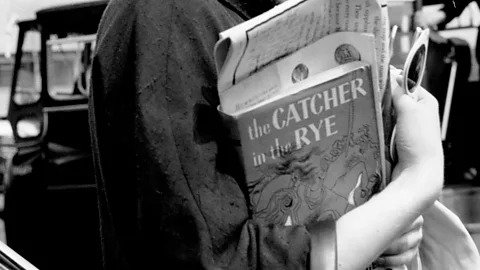

The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger, 1951

Poor Holden Caulfield. Mired in a funk for more than half a century, the angst-ridden ‘everyteen’ is now regarded by the cool kids as being a bit – well, self-indulgent. His ennui is, if not exclusively a rich-white-boy problem, then certainly nothing compared with looming climate collapse and other woes weighing on the minds of his 21st-Century peers. Plus, in the era of helicopter parenting and geo-tagging, not to mention hyper-vigilant mental-health awareness, the idea that a depressed teen could simply go Awol in New York City for a couple of days is increasingly hard to indulge.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAtlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand, 1957

As a philosopher, Rand gave the world Objectivism, idealising laissez-faire capitalism and the pursuit of self-interest. Accordingly, her novel tells the 1,200-page story of a dystopian US, buckling beneath burdensome rules and regulations. Mauled by critics, it became a word-of-mouth bestseller thanks in part to superfan Nathaniel Branden, who proved his allegiance by memorising her earlier work, The Fountainhead – all 750 pages of it. But adoration can be a mixed blessing: while Atlas is still revered by libertarians and political conservatives, the nature of its latter-day fans – a host of President Trump’s associates among them – has helped alienate a new generation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Beach by Alex Garland, 1996

You likely had to be there to even begin to get how The Beach exerted such a hold over its readers. ‘There’ being not its exotic location – an idyllic island off Bangkok – but the 1990s, when rave culture ruled. It was a moment ripe for this amphetamine-fuelled, hallucinogenic novel whose disaffected narrator has been given directions to a supposedly pristine Utopia. Here’s the catch: Richard is searching for a truly authentic experience, something that few even pretend to want any longer, preferring instead to enquire about what filter’s been used. Plus, who’d know what to do with a hand-drawn map these days?

Alamy

AlamyIron John by Robert Bly, 1990

A consciousness-raising polemic based on a German folk tale, this is the book that inspired a generation of middle-aged men to braid leaf crowns and circle dance bare-chested in the woods. As with so many books on this list, its flaws have been magnified by the passage of time. Utterly devoid of irony and blinkered by his orientation as a straight white bloke, its lute-strumming (oh yes) author is just too easy to send up. And then there are the honking great phallocentric metaphors that he just can’t let go of… We may well need to redefine masculinity, but re-wilding doesn’t seem the optimal way of going about it.

The Outsider by Colin Wilson, 1956

In its heyday, every Angry Young Man was paging through this rambling study of the outsider in Western literature. Written by a 24-year-old with apparently neither formal education nor a home (he was homeless and sleeping on London’s Hampstead Heath), it won glowing reviews. Then, just two years later, Wilson’s second novel was so comprehensively panned that The Outsider was re-evaluated and found badly lacking. Not that it inhibited Wilson, who went on to write more than 100 further books, comparing himself to Nietzsche, and accusing Shakespeare of having a mind “like a female novelist”. And no, he did not mean that as a compliment.

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway, 1952

Hemingway’s supposed masterpiece of a novella describes a luckless old fisherman who sets sail on a solo fishing expedition and finds himself in a three-day tussle with a gigantic marlin. Lacking the complex plots and satisfying character arcs of his better work, its wisdom includes pearls such as “pain does not matter to a man”. There are alternative readings of this text but so long as ‘Papa’s’ persona as a bullfighting brawler retains its power, it will remain a paean to faltering virility that’s likely to put readers off his entire oeuvre.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the Road by Jack Kerouac, 1957

Based on a road trip from New York to Mexico with Beat muse Neal Cassady, Kerouac wrote what would become the Beatnik’s bible in just three weeks. It took six years to get published and more than half a century later, it exudes tiresome stoner machismo. Kerouac pokes fun at gay people, and isn’t much better where women and black people are concerned. A few years back, a spate of books and films inspired only a flicker of revived interest in his legacy. Boorish egotist or inspired prophet? The jury isn’t just out, it left the building long ago, dancing after the hippies who supplanted the Beats.

Alamy

AlamyThe Rules by Ellen Fein and Sherrie Schneider, 1995

Men have The Game; women have The Rules, a manipulative, oddly heartless bestseller whose slavish followers (they’re said to include Blake Lively) were gluttons for dictums like don’t talk, don’t have curly hair, don’t even think of returning that call. Never mind the feminist critiques – its opinion of men is so low you’re left wondering why any of us would want to land such a catch in the first place. In 2013, the book was updated for the era of internet dating and sexting, but it still seems positively Victorian in the context of a cultural marker like Lena Dunham’s Girls.

Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach, 1970

So, yes, Jonathan Livingston Seagull really is a seagull, but he’s a seagull with aspirations, a non-conformist who yearns to soar above the flock and up into the heavens, just as the book itself conquered the bestseller charts back in the day. Its saccharine idealism isn’t made any more palatable by learning that Richard Nixon’s FBI director, L Patrick Gray, ordered all his staff to read it, and a 1973 movie adaptation, complete with Neil Diamond soundtrack, did it no favours either. Film critic Roger Ebert summed it up: “This has got to be the biggest pseudocultural, would-be metaphysical rip-off of the year”.

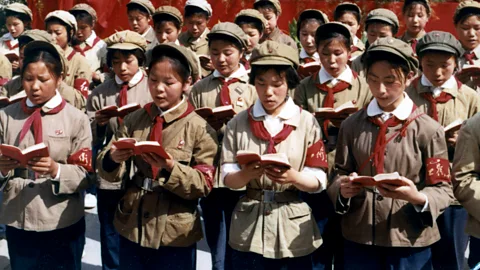

Little Red Book by Mao Zedong, 1964

During China’s Cultural Revolution it was essential to own and carry one of these pocket-sized volumes of Chairman Mao’s aphorisms, making it second only to the Bible in terms of copies printed. It was also adopted by Western hippies, becoming a must-have accessory for every blissed-out fellow traveller, but it’s suffered doubly in the decades since. For a start, there’s the matter of Mao’s involvement in torture, mass killings and the devastating famine that resulted from his Great Leap Forward.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInfinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, 1996

The story of a reformed addict who navigates enormous personal trauma without falling off the wagon, this novel’s fate is a melancholy example of how writers can become victims of their own cultdom. Since his suicide in 2010, DFW’s fans have canonised him. The hero worship has rendered books like Infinite Jest – whose physical heft makes it big enough to be used as a weapon – symbols of ‘bro-lit’. It also made stories about his abusive treatment of women harder to hear. This may still be a cult read among a certain type of young man, but female readers have by and large dropped it like a sweaty jockstrap.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

.jfif)

Post a Comment