On 29 October 1969, two scientists established a connection between computers some 350 miles away and started typing a message. Halfway through, it crashed. They sat down with the BBC 55 years later.

At the height of the Cold War, Charley Kline and Bill Duvall were two bright-eyed engineers on the front lines of one of technology's most ambitious experiments. Kline, a 21-year-old graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and Duvall, a 29-year-old systems programmer at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), were working on a system called Arpanet, short for the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network. Funded by the US Department of Defense, the project aimed to create a network that could directly share data without relying on telephone lines. Instead, this system used a method of data delivery called "packet switching" that would later form the basis for the modern internet.

It was the first test of a technology that would change almost every facet of human life. But before it could work, you had to log in.

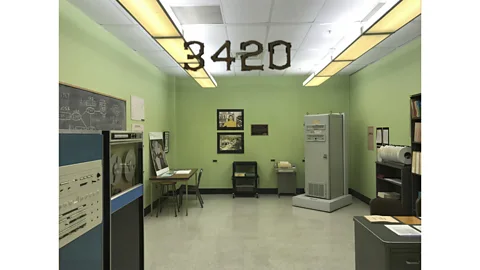

Kline sat at his keyboard between the lime-green walls of UCLA's Boelter Hall Room 3420, prepared to connect with Duvall, who was working a computer halfway across the state of California. But Kline didn't even make it all the way through the word "L-O-G-I-N" before Duvall told him over the phone that his system crashed. Thanks to that error, the first "message" that Kline sent Duvall on that autumn day in 1969 was simply the letters "L-O".

Courtesy of Charley Kline

Courtesy of Charley KlineThey got their connection up and running about an hour later after some tweaks, and that initial crash was just a blip in an otherwise monumental achievement. But neither man realised the significance of the moment. "I certainly didn't at that time," Kline says. "We were just trying to get it to work."

The BBC spoke to Kline and Duvall for the 55th anniversary of the occasion. Half a century later, the internet has shrunk the whole world down to a small black box that fits in your pocket, one that dominates our attention and touches the furthest reaches of lived experience. But it all started with two men, experiencing just how frustrating it is when you can't get online for the very first time.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

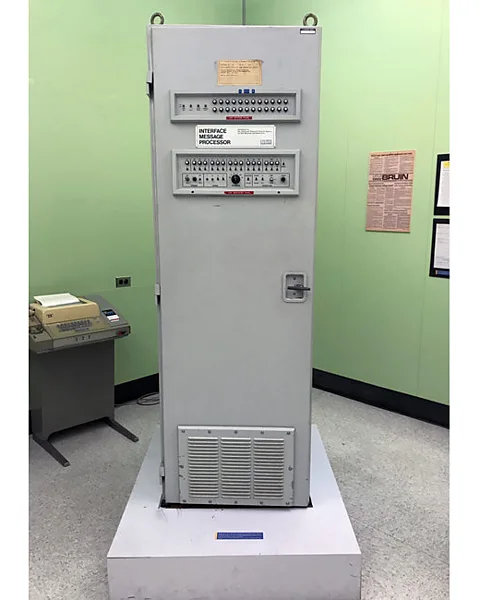

Can you describe the computers that enabled Arpanet? Were these massive, noisy machines?

Kline: They were small computers – by standards of that time – about the size of a refrigerator. They were somewhat noisy from the cooling fans, but quiet compared with the sounds from all the fans in our Sigma 7 computer. There were lights on the front that would blink, switches that could control the IMP [Interface Message Processor], and a paper tape reader that could be used to load the software.

Duvall: They were in a rack big enough to hold a complete set of sound equipment for a large show today. And they were thousands if not millions or billions of times less powerful than the processor in an Apple Watch. These were the old days!

Take us inside that moment when you started typing L-O.

Kline: Unlike websites and other systems today, when you connected a terminal to the SRI system nothing happened until you typed something. If you wanted to run a programme, you first needed to login – by typing the word "login" – and the system would ask for your user name and password.

As I typed a character on my terminal – a teletype model 33 – it would get sent from my terminal to the programme I wrote for the SDS Sigma 7 computer. That programme would take the character, format it into a message and send it to the Interface Message Processor. When it was received by SRI's system, [it] would treat [the message] as if it came from a local terminal and would process it. It would "echo" the character [replicate it on the terminal]. In this case, Bill's code would take that character and format it into a message and send it to the IMP to go back to UCLA. When I received it, I would print it on my terminal.

UCLA

UCLAI was on the phone with Bill when we tried this. I told him I typed the letter L. He told me he had received the letter L and echoed it back. I told him that it printed. Then I typed the letter O. Again, it worked fine. I typed the letter G. Bill told me his system had crashed, and he would call me back.

Duvall: The UCLA system did not anticipate that it would receive G-I-N after Charlie had typed L-O, so it sent an error message to the SRI computer. I don't recall exactly what the message was, but what happened next was due to the fact that the network connection was much faster than anything seen before.

The normal connection speed was 10 characters per second whereas the Arpanet could transmit characters at up to 5,000 characters per second. The result of this message being sent from UCLA to the SRI computer flooded the input buffer which only expected 10 characters per second. It was like filling a glass with a fire hose. I quickly discovered what had happened, changed the buffer size and rebuilt the system, which took about an hour.

Emmanuel LaFont

Emmanuel LaFontDid you realise this could be a historic moment?

Duvall: Not really. It was another step forward in the larger context of the work we were doing at SRI which we did believe would have a large impact.

When Samuel Morse sent the first telegraph message in 1844, he had an eye for drama, tapping out "What hath God wrought" on a line from Washington, DC to Baltimore, Maryland, US. If you could go back, would you have typed something more memorable?

Kline: Of course, if I had realised its importance. But we were just trying to get it to work.

Duvall: No. This was the first test of a very complicated system with a lot of moving parts. To have something this complex work in the very first test was dramatic in and of itself.

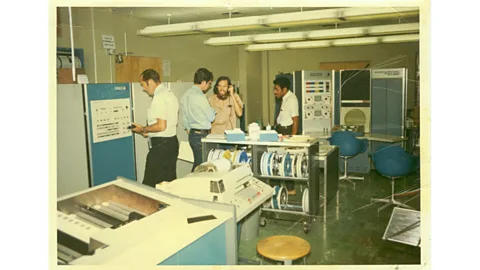

What was the atmosphere like when the message was sent?

Duvall: We were each alone in our respective computer laboratories at night. We were both happy to have had such a successful first test as the culmination of a lot of work. I went to a local "watering hole" and had a burger and a beer.

Kline: I was happy that it worked and went home to get some sleep.

What did you expect Arpanet to become?

Duvall: I saw the work we were doing at SRI as a critical part of a larger vision, that of information workers connected to each other and sharing problems, observations, documents and solutions. What we did not see was the commercial adoption nor did we anticipate the phenomenon of social media and the associated disinformation plague. Although, it should be noted, that in [SRI computer scientist] Douglas Engelbart's 1962 treatise describing the overall vision, he notes that the capabilities we were creating would trigger profound change in our society, and it would be necessary to simultaneously use and adapt the tools we were creating to address the problems which would arise from their use in society.

What aspects of the internet today remind you of Arpanet?

Duvall: Referring to the larger vision which was being created in Engelbart's group (the mouse, full screen editing, links, etc.), the internet today is a logical evolution of those ideas enhanced, of course, by the contributions of many bright and innovative people and organisations.

Kline: The ability to use resources from others. That's what we do when we use a website. We are using the facilities of the website and its programmes, features, etc. And, of course, email.

The Arpanet pretty much created the concept of routing and multiple paths from one site to another. That got reliability in case a communication line failed. It also allowed increases in communication speeds by using multiple paths simultaneously. Those concepts have carried over to the internet.

Courtesy of UCLA

Courtesy of UCLAAs we developed the communications protocols for the Arpanet, we discovered problems, redesigned and improved the protocols and learned many lessons that carried over to the Internet. TCP/IP [the basic standard for internet connection] was developed both to interconnect networks, in particular the Arpanet with other networks, and also to improve performance, reliability and more.

How do you feel about this anniversary?

Kline: That's a mix. Personally, I feel it is important, but a little overblown. The Arpanet and what sprang from it are very important. This particular anniversary to me is just one of many events. I find somewhat more important than this particular anniversary were the decisions by Arpa to build the Network and continue to support its development.

Duvall: It's nice to remember the origin of something like the internet, but the most important thing is the enormous amount of work that has been done since that time to turn it into what is a major part of societies worldwide.

The modern web is dominated not by government or academic researchers, but by some of the largest companies in the world. How do you feel about what the internet has become? What are you most concerned about?

Kline: We use it in our daily lives, and it is very important. It's hard to imagine ever not having it again. One of the benefits of it being so open and not controlled by a government is that new ideas can get developed, such as online shopping, banking, video streaming, news sites, social media, and more. But because it has become so important to our lives it is a target for malicious activity.

We hear constantly about how things have been compromised. There is a tremendous loss of privacy. And the big companies (Google, Meta, Amazon and internet service providers such as Comcast and AT&T) have too much power in my opinion. But I am not sure of the right remedy.

Courtesy of UCLA

Courtesy of UCLADuvall: I think that there is great danger in the domination by any single entity. We have seen the power of disinformation in directing policy and elections. We have also seen the power of companies in influencing the direction of social norms and the formation of adults and young adults.

Kline: One of my biggest fears has been about the spread of false information. How many times have you heard someone say, "I saw it on the internet". It was always possible to spread false information, but it would cost money to send out mailers, put up a billboard or take out a TV ad. Now it is cheap and easy. And as it reaches millions of people, it gets repeated and treated as fact.

Another fear is that as more and more critical systems have moved onto the internet it becomes easier to cause a serious disruption if those systems are taken down or compromised. For example, not only communications systems but banking, utilities, transportation, etc.

Duvall: It has great power but, not heeding Engelbart's warning in 1962, we have not effectively used the power of the internet to manage the social impact.

Are there any lessons from your time at Arpanet that could make it a better place for everyone?

Kline: While the openness of the internet allows experimentation and new uses, the lack of control can lead to compromises. Arpa kept some control of the Arpanet. That way they could make sure that everything worked, make decisions about which protocols were required, deal with issues such as site names and other issues.

More Like This

● Google just updated its algorithm. The Internet will never be the same

● 'Postcards are the email of their day': How cat memes went viral 100 years ago

● We're losing our digital history. Can the Internet Archive save it?

While Icann [the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers] still manages some of that, there have been international disagreements about how to move forward and whether the US has too much control, etc. But we still need some controls to keep the network functional. Also, since the Arpanet was relatively small, we could experiment with major changes in design, protocols, and more. That would be extremely hard now.

Duvall: We are standing on the edge of a precipice with AI and the reflexive access it has to everyone who graces the internet. The internet had explosive growth and development – some of it socially damaging – in the early days. AI now stands at that threshold, and is inseparable from the internet. And it is not unreasonable to call AI an existential threat. The time to recognise the dangers as well as the promise is now.

--

For timely, trusted tech news from global correspondents to your inbox, sign up to the Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

Post a Comment